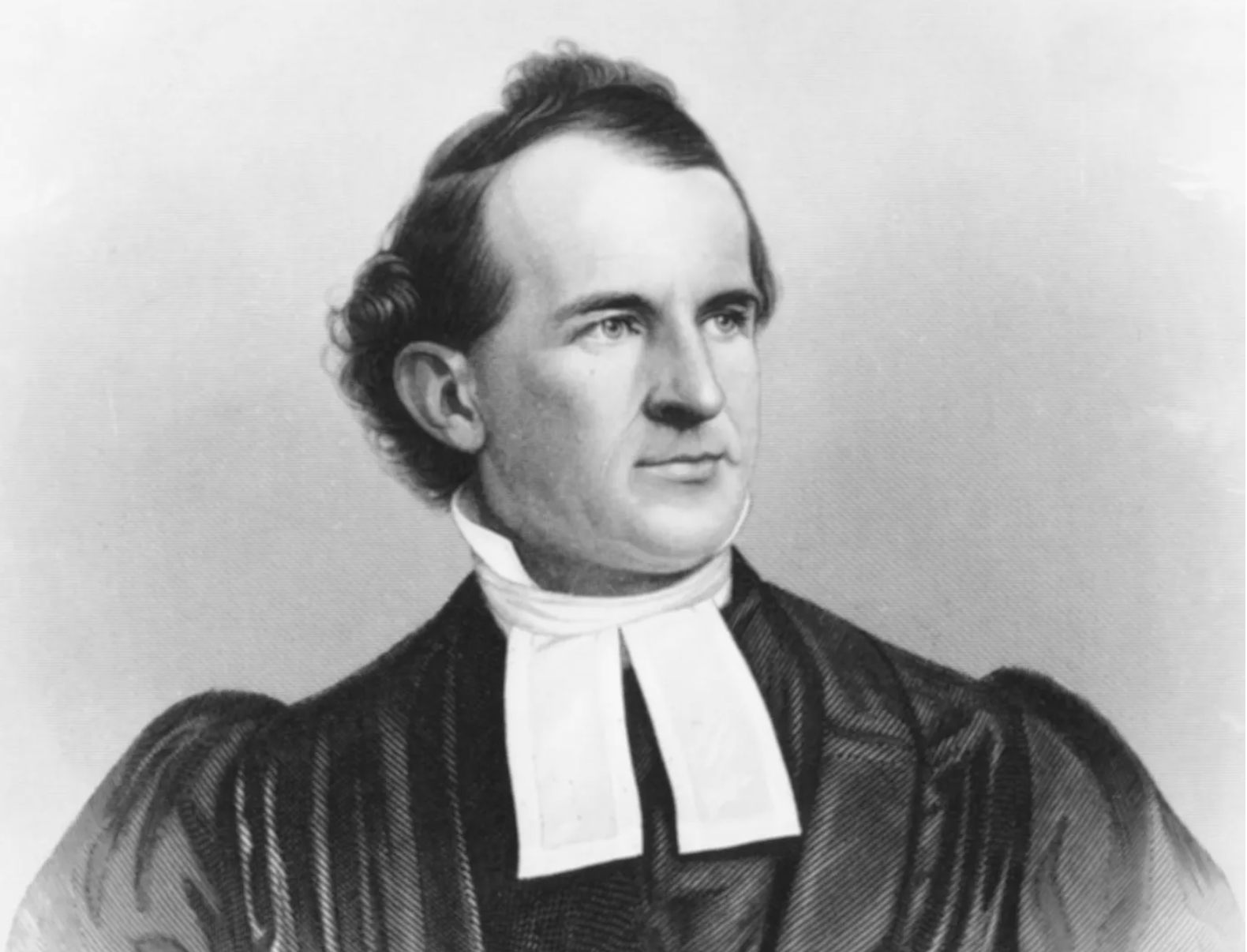

In 1861, Bishop Cummins delivered a sermon in Philadelphia, in behalf of the Bishop White Prayer Book Society, and in 1867, after he had been consecrated to the Episcopate, as Assistant Bishop of Kentucky, he preached before the Convention of that Diocese that same sermon, rewritten, with additional matter.

“Again, we claim this high position for the Prayer Book because it is committed to no human system of theology, but is broad enough and comprehensive enough to embrace men who differ widely in their interpretations and definitions of Scriptural truth.

It is indeed a peculiar glory of the Prayer Book that it is marked by the “elastic tenderness of a nurse who takes into account the varying temperaments and dispositions of children;” not by the rigid precision of an imperious taskmaster, who would prostrate into a procrustean bed all the varieties of human feeling and human conscience. It bears upon its very fore-front Augustine’s motto, “In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; in all things, charity.” They who framed the liturgy recognized the truth that their work was not for a day, but for all time; not for a nation or a denomination, but for a great Catholic Church, which, in God’s good time, might be co-extensive with the earth.

Hence, they were careful that its doctrinal teachings should be set forth only as the Bible sets them forth, and as they were embodied in ancient creeds and liturgies, purified from all the errors which were the growth of a later and darker age. They called no man master on earth; they followed not Augustine, nor Luther, nor Calvin, but Christ and His Apostles. Hence the theology of the Prayer Book is not the confession of Augsburg, nor that of the Synod of Dort, nor yet of the Westminster Assembly. It is not Lutheranism, nor Calvinism, nor Arminianism; but better than all, it embraces all that is precious and of vital truth in each of these systems, yet committing itself to none; and a disciple of each of these schools may find in it that which gives “rest to his soul.”

Does the follower of Calvin find the doctrine of election a “doctrine full of sweet, pleasant, and unspeakable comfort to the soul of a godly person?” So teaches the seventeenth article of religion of the Prayer Book. Does the Arminian hold nothing to be more vital and essential than the doctrine of the free, unlimited, unrestricted offer of salvation to all mankind? He finds it running like a silver thread through all the texture of these beauteous garments of the Bride of Christ. Does the Wesleyan regard it as the blessed privilege of a child of God to know God as a reconciled father, who, in Christ, has put away his sins, and given him joy and peace in believing? Where else is such a truth so fully recognized as in those seraphic strains of devotion which lift the soul into holy communion with God, and cause it to realize its acceptance in the beloved? Does the Lutheran place a high value upon the worthy partaking of the Sacrament of Christ’s body and blood? Surely, the lofty, glowing language of the communion office is fitted to meet the deepest longings of the soul, as it feeds on Christ in the heart by faith with thanksgiving.

Are not these facts evidence that the system of the Prayer Book is the system of the Bible? This is the boast, this is the honor of our Church. Let her willingly submit to the ignorant reproach that men of every creed can find in her something to favor their views, whilst she shares this reproach with the Word of God. It is this fact which fits her for universality; in this fact is found her chief power.”

Bishop Cummin’s Sermon in Defence of the Prayer Book.

Source and Full sermon text: http://anglicanhistory.org/usa/rec/four.html

Leave a ReplyCancel reply