The Vernacular Language

Today, the term “vernacular” implies the local language spoken by a particular people. For instance, English is the common language in the United Kingdom, Cantonese in Hong Kong, and various Dravidian tongues like Tamil, Telugu, or Malayalam are used by South Indian people. This diversity of languages has significant implications for Bible translations. Unfortunately, I often find myself disappointed with efforts to make the Bible more accessible by “dumbing down” the language instead of encouraging readers to grow in their understanding.

While I am not a King James Onlyist, our Sunday services utilize the King James version. Some individuals complain about the difficulty of understanding the “thees and thous,” but I believe this perspective is misguided. We live in a time often described as the most literate era of Christendom, yet we seem to have grown lazy. Instead of taking a few moments to learn the language and engage with the text, we seek everything pre-digested and tailored to our comfort. However, the Bible is a profound and substantial book that requires us to engage with it actively, like chewing meat before swallowing.

The Reformation struggle against ministering “in a tongue not understood of the people.” (Article XXIV, 39 Articles) produced a beautiful English liturgy and the King James Bible. These vernacular translations were not the everyday language used by 16th-century English peasants; they did not “speak this way” in their daily lives. Instead, these translations established a standard for the national language that reflected the dignity of their God. The King James Bible and Book of Common Prayer were intentionally written to be elevated Jacobean prose above the common speech of the people. The King James Version Defended by Edward Hills does a great job defending this perspective.

Pre-Reformation English

The Reformation was the second time England had placed a national significance on the English language. English vernacular has made its way into Celtic Christianity through the Lindisfarne Gospels (circa 715) which were an English translation of the Latin. In the 9th century, King Alfred the Great set English (of a pre-Norman Saxon dialect) as the legal and academic language of the Kingdom. King Alfred was also picking up the cultural precedent began by the Venerable Bede (AD 672-735) who had translated the Gospel of St. John into an older dialect of English.

The Latin Bible to King James

The Latin Bible called the “Vulgate” was translated from Greek, Latin, and Hebrew texts in the 4th century by St. Jerome. The works was partly a revision of previous Latin manuscripts and is often credited as a the first translation to check its work against Hebrew sources. Previous Bible translations depended on the Greek Old Testament (Septuagint), but Jerome built his work from the Hexapla of Origen. Origen’s work used six (hence “hex”) columns of scripture to compare various manuscript traditions.

The Tyndale Bible, translated from Latin into English in 1525, was the result of collaboration between William Tyndale and Miles Coverdale, leading to the creation of the first complete English Bible translation. Around the same time, Thomas Cranmer, then a priest, was sent to the continent to garner support for Henry VIII’s annulment. During his time in Germany, Cranmer encountered the Lutheran theologian Andreas Osiander and secretly married his daughter. Osiander, a translator himself, had published a corrected edition of the Vulgate Bible using Hebrew sources. All these Protestant scholars followed an “ad fontes” or “back to the sources” approach to biblical scholarship, seeking to go beyond the Latin translations.

By 1539, Henry VIII mandated that every parish church in England should provide its parishioners with a copy of the English Bible. The Great Bible, based on the translation work of John Rogers, incorporated portions from the Tyndale and Coverdale Bibles. This Bible became known as “The Chained Bible” because copies were frequently chained to reading desks attached to pillars within churches to deter theft.

The Geneva Bible and Bishop’s Bible

After the death of Henry’s son, Edward VI, the English crown passed to Mary Tudor, also known as “Bloody Mary.” Being a Roman Catholic, she sought to reverse the cause of the Reformation in England, forcing many of the country’s Reformation scholars to flee to the continent. This led to the emergence of a new English translation known as the Geneva Bible, which featured explanatory notes in its margins, presenting Reformation doctrine alongside the main text. These marginal notes were heavily influenced by the Reformed or Calvinist theology of John Calvin, the pastor of the Genevan Church in Switzerland. The Puritan party within the Church of England found alignment with many ideas presented in the Geneva Bible’s notes.

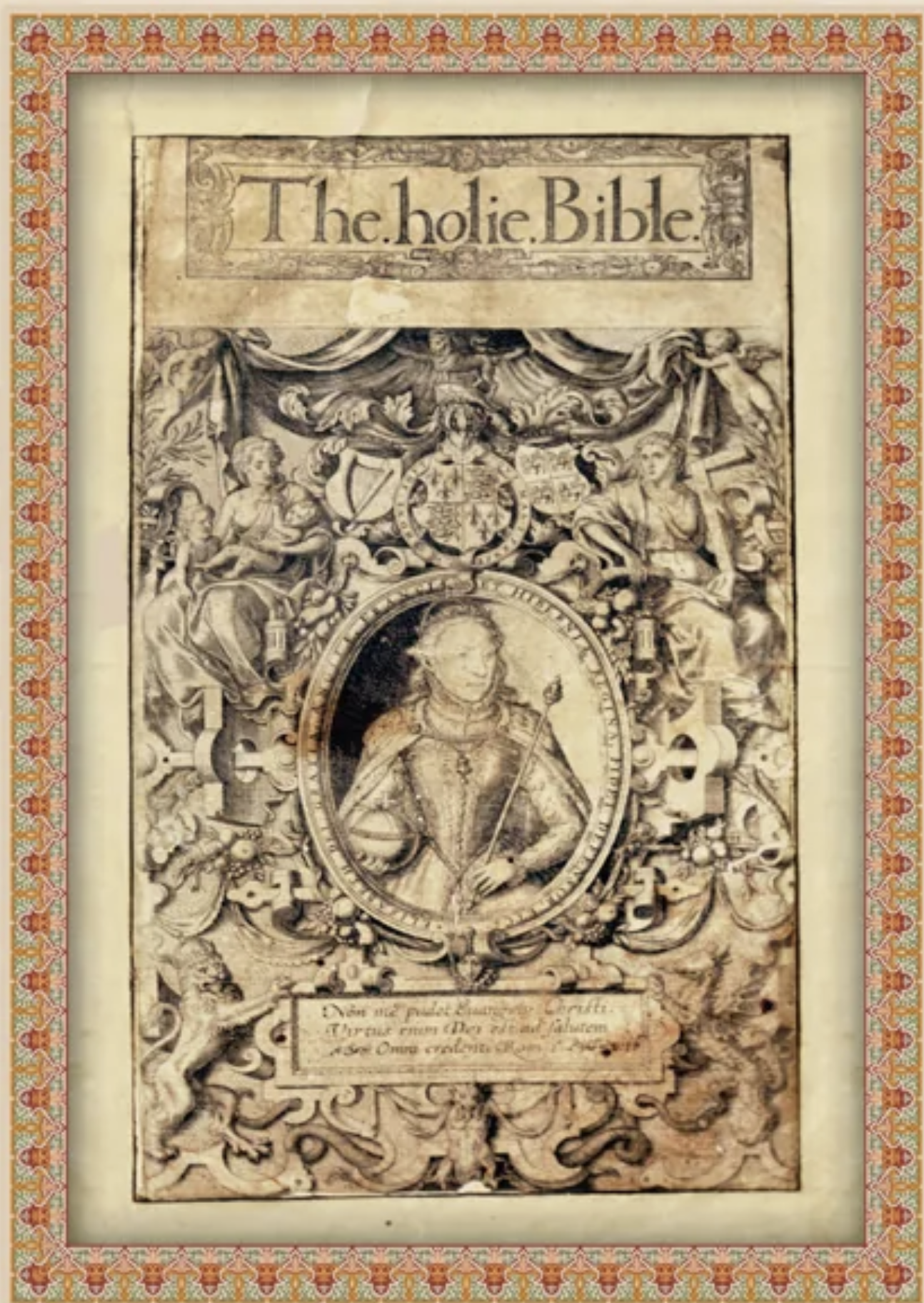

During Queen Elizabeth I’s reign, the Bishop’s Bible was created under Archbishop Parker. While the queen was less sympathetic to the Puritans, she remained staunchly Protestant. It was during Elizabeth’s time that the church promulgated the 39 Articles (1563), requiring clergymen within the English Church to adhere to Protestant theology. Nevertheless, Elizabeth sometimes found herself in disagreement with Calvinist interpretations of certain articles, foreshadowing potential future conflicts between Puritans and the Protestant English monarchy. Notably, the Bishop’s Bible lacked marginal notes and its text closely resembled that of the Geneva Bible.

Despite the authorization of the King James Bible, the Geneva Bible retained its popularity well into the 17th century. Large numbers were imported from Amsterdam, and it became the Bible carried to America by the Pilgrims.

The King James Bible

In response to the death of Queen Elizabeth I, the Puritan party within the Church of England saw King James VI and I as an opportunity to continue the reform of the English church. James was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, and was influenced by the “presbyterian” Kirk, which strongly embraced the theology of Geneva and the Calvinists. He was descended from the Scottish kings through Robert the Bruce and from the English Tudors through his great grandmother Margaret Tudor, sister of Henry VIII. The more radical Scottish reformer, John Knox, preached at James VI’s coronation in Stirling in 1567.

King James’s ascension marked a union of Scotland and England, symbolized today in the “Union Jack” flag, which combines the blue Scottish saltire cross of St. Andrew with the red English cross of St. George. King James aimed to use the new Bible as a means to unite the divided religious settlements between the English and Scots. Although it’s uncertain if James intended it himself, his efforts bore resemblance to King Alfred the Great’s initiative in promoting the English bible.

Alister McGrath notes:

“With serious religious tensions growing in England at the time of his accession to the throne, the image of the king giving the Bible to his people was more than a piece of religious theater; it was the essential means by which national unity might be secured at a time of potential fragmentation.”

In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, a Language, and a Culture, Alister McGrath

In 1604, King James called “The Hampton Court Conference,” seeking “a single translation… To be read in the whole Church,” as he put it. The balance of the King and his committee is well described by British historian Richard Cavendish:

“The King had a lively intelligence, a sharp tongue and a high regard for the English Church with its stately retinue of supportive bishops and himself as supreme governor. At the same time he was a shrewd man, with much experience in Scotland of reconciling moderates with radicals in religious matters, and though he had once described Puritans as ‘very pests’ in Church and State, he explained that he had meant only the most extreme and irritating ones. He decided to preside personally over a formal conference at Hampton Court, attended by Archbishop Whitgift, who had been at Canterbury for twenty years, and eight bishops in their uniform of caps and surplices, which Puritans disliked. With them were five deans, including Lancelot Andrewes of Westminster, and four carefully selected representatives of moderate puritanism. They were John Reynolds, Master of Corpus Christi, Oxford, and former Dean of Lincoln, Laurence Chaderton, Master of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, a Suffolk rector named John Knewstubs (who denounced surplices as garments the priests of Isis had worn) and a silent Buckinghamshire clergyman called Thomas Sparke. Bishops and Puritans knew each other well and in several cases were old friends.”

History Today Volume 54 Issue 1 January 2004

Leave a ReplyCancel reply